Source: Heritage Communications

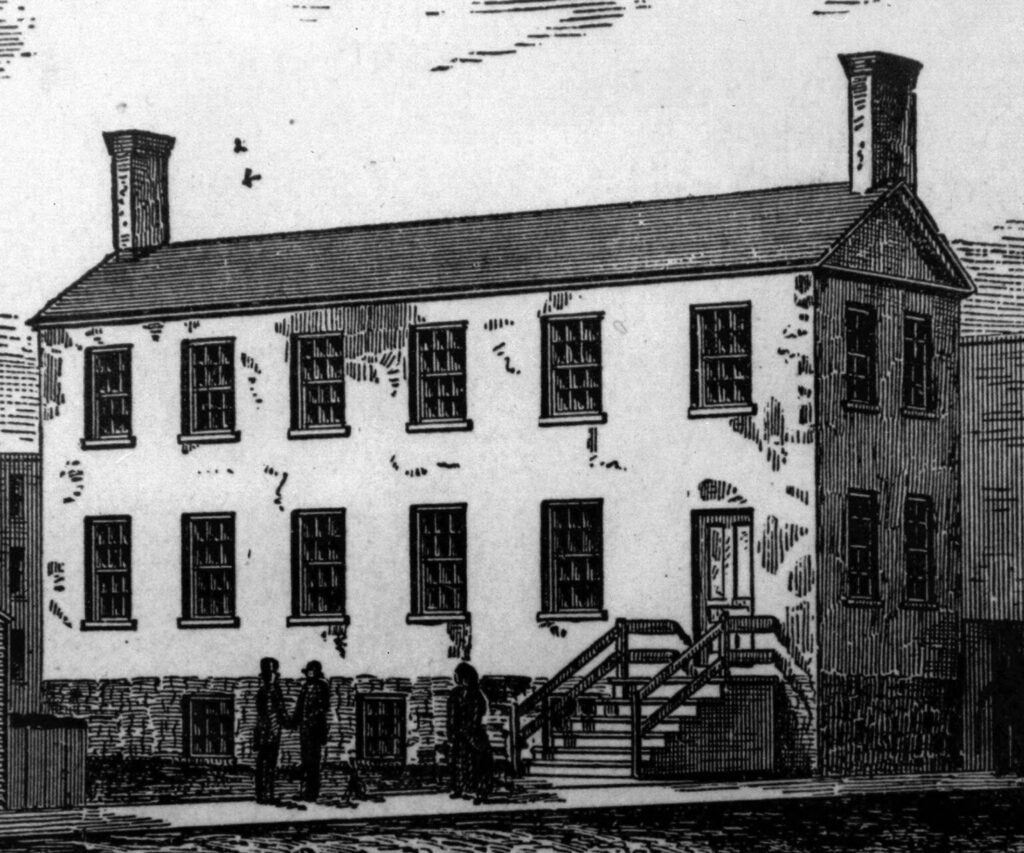

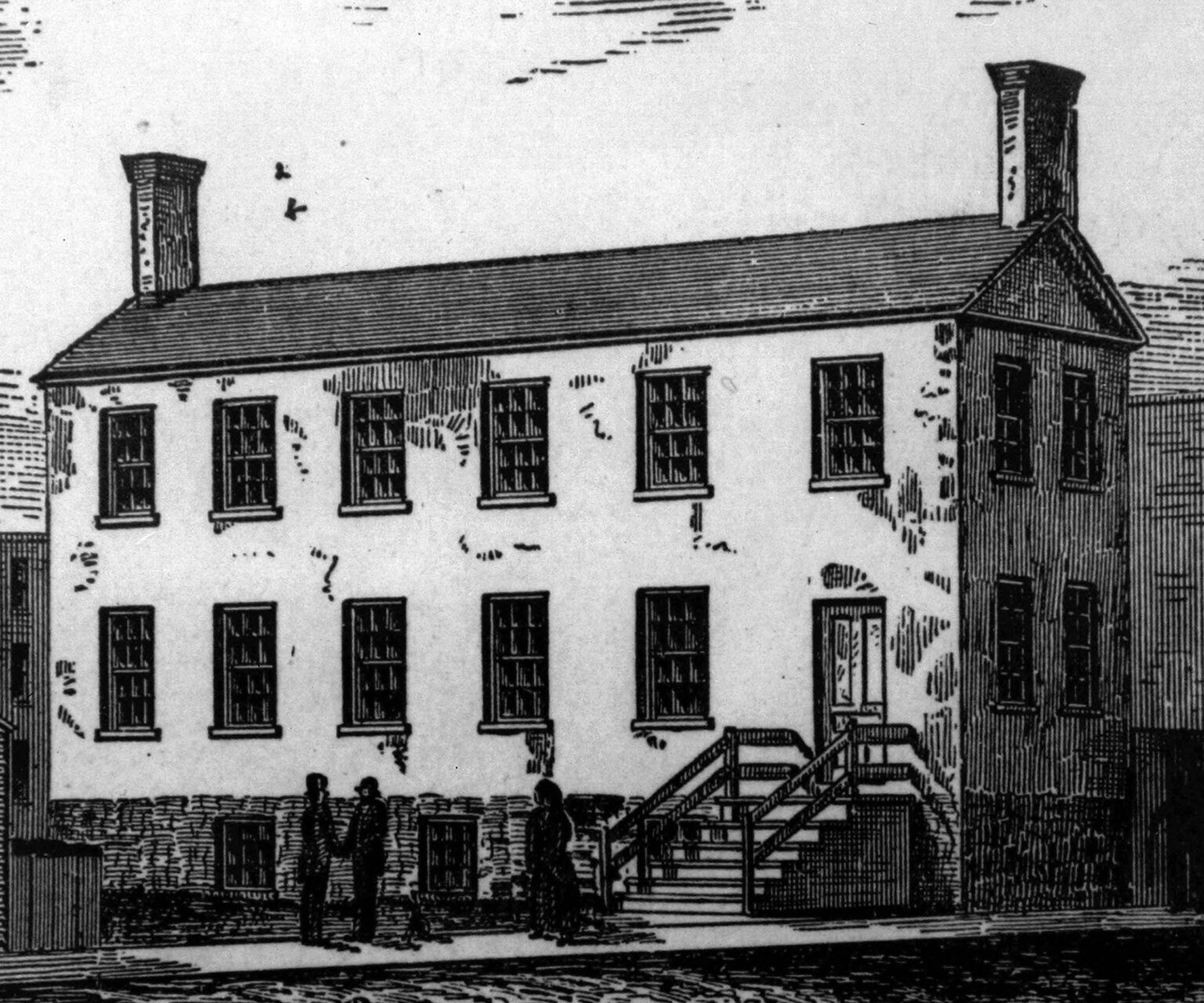

U-M’s first building, on Bates Street in Detroit, also housed the state’s first Sunday school. (Bentley Historical Library)

U-M’s first building, on Bates Street in Detroit, also housed the state’s first Sunday school. (Bentley Historical Library)

On a Sunday morning in the fall of 1818, young people in the village of Detroit made their way into the new academy built by the fledgling University of Michigania. Eight teachers awaited them.

It was the inaugural class of the first Sunday school held in the Territory of Michigan.

The school’s roots traced back to Aug. 26, 1817, and the establishment of the Catholepistemiad, or the University of Michigania. Within a month, workers had started constructing a classroom building on Bates Street, and by the following fall, the school opened with two teachers and 11 students.

The initial U-M classes were at the elementary school level, with parents paying a small subscription fee for teacher salaries, books and furniture.

For families unable to pay, U-M teacher Lemuel Shattuck established the Sabbath school, opening its doors on Oct. 4, 1818. His early objective as the school superintendent was “to instruct children and others in the art of reading, free of expense, and to stimulate them to exertion in acquiring the rudiments of knowledge.”

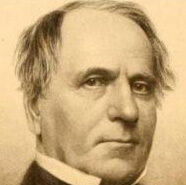

Lemuel Shattuck

U-M’s founders had lured the 25-year-old Shattuck from a teaching position in Albany, New York, to the Michigan frontier earlier that year. On weekdays he and a second U-M teacher, Hugh M. Dickie, held classes for nearly 100 paying students. Shattuck taught students at the primary level, with lessons in reading, writing, arithmetic, grammar and geography. At the same time, Dickie conducted a classical academy for older students learning Greek, Latin, French and sciences.

The Sunday school classes, while focused on overcoming illiteracy, also aimed to instill good morals. “Our youth have been usually left to grow up in the practice of vice without restraint, and uninfluenced by the motives a religious education inculcates,” Shattuck said. Students memorized Bible verses, Christian principles and the lyrics of hymns.

The Protestant-based classes were offered both to white children and young African Americans, whom Shattuck said were particularly in need because of being excluded from “the usual privileges of society.” Students ranged in age from 3-19.

Shattuck continued to operate the Sunday school until December 1821, when he left Detroit, and local Presbyterians took control of lessons.