Heather Ann Thompson.

Heather Ann Thompson.

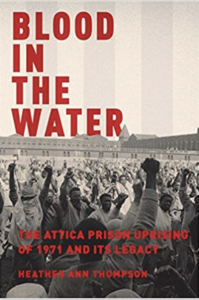

University of Michigan professor Heather Ann Thompson, whose family moved to Detroit when she was a teen, is an acclaimed historian who received the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in History for her book Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy.

Raised primarily in Detroit’s North Rosedale Park neighborhood, Thompson considers the city a great influence in her work to understand race relations, mass incarceration, and America’s justice system. After graduating from U-M with her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in History, she completed her PhD at Princeton University before teaching at UNC Charlotte and Temple University. She returned to U-M in 2015 as a full-time professor.

Thompson co-founded U-M’s Carceral State Project, an organization created to understand and combat mass incarceration through collaboration between academia and community organizations. The project recently received an important grant from U-M’s Humanities Collaboratory to begin the Documenting Criminalization and Confinement initiative. This endeavor will be the first comprehensive qualitative and quantitative report on criminalization and the conditions of confinement in America.

How did growing up in Detroit influence your work?

Thompson: Growing up in Detroit, particularly in the late 1970s and early 80s, you couldn’t help but wonder what had happened to the city. There was a lot of social dislocation and economic devastation. Every newspaper article written about the city was negative, and it was reviled by every pundit. It struck me that there was something deeply racialized in their interpretation. So when I got to U-M as an undergraduate, I very much wanted to understand the city that I had come from. Even then, I realized that understanding what Detroit had gone through, both good and bad, was a means of understanding other cities around the country. I actually grew up there and, thus, came at it from a very particular vantage point. Growing up as a white kid in an overwhelmingly black city very much impacted my perspective of the city. For example, others were writing about the collapse of the city, but to me, it was always the site of extraordinary black accomplishment and success, and I wanted to understand the roots of that.

After writing about race-related issues in Detroit and nationally, was there a natural progression into exploring mass incarceration?

Thompson: One would think that such a progression would be obvious given how much incarceration has devastated the city, but I didn’t begin working on this until a bit of a lightbulb had finally turned on for me while I was working on my book about the Attica prison uprising of 1971. To be sure, something really devastating was going on around all of us but, both as citizens and scholars, it was hard to really see what it was until some time had passed. As it turns out, the first book I wrote on Detroit was fundamentally about incarceration and policing, and I was in high school as the drug war began with a vengeance, but funnily enough, but I didn’t see it through that lens until years later. While writing on Attica, though, I began to think a lot about Detroit and finally understand that what had happened to that city by the 1980s wasn’t just deindustrialization and white flight; it was also major policy changes that had led to over-policing and mass incarceration. When I finally did “see” those issues, and I think this is true of many of us who have begun recognizing the devastating effects of mass incarceration, I couldn’t unsee them, and I not only had to write about it, but also try to do something about it.

Could you discuss your Pulitzer Prize winning book Blood in the Water and why you felt it necessary to create such a comprehensive work about the Attica Prison Uprising of 1971?

Thompson: It was a book that took more than 13 years to complete, primarily because all of the records related to this dramatic prison uprising for better conditions are still sealed by the state of New York. So, in order to tell this story, it was a challenge to find out who had the records and who was being covered up. It was an extraordinary research journey. In time, I met many of the survivors and also had the sheer luck of happening upon key records that the state did not know I had found. Via those, I was able not only to tell the story of what happened in 1971, but also to shine a light on the police who had committed terrible crimes back in 1971 and have been protected ever since. Furthermore, I began to see key connections between Attica and today and tried in my book to help people understand why our country took the punitive turn that it did. The book was a real labor of love, and it really changed my life. It was the writing of that book that persuaded me how important prisons and incarceration really are in America.

How far have we come as a country in relation to the issues you have studied? Detroit specifically?

Thompson: I think we’re living in a very important moment. On the one hand, we’re poised for positive change with incredible energy to make our criminal justice system more just, and nowhere are we seeing that more than in Detroit. There are so many people on the ground working hard to overhaul our justice system — incredible work going on at places such as the Detroit Justice Center and the American Friends Service Committee. At the state level as well, strides are being made to have records expunged, to reduce sentences, and to make it possible for those who have a record to get a job or housing. On the other hand, it is a constant battle to educate the American public that they are not safer with more prisons. In fact, criminalizing people has terrible, unintended consequences. I just returned from Norway and Finland, and I am utterly persuaded that if other countries can treat those who commit harm or are addicted or simply are poor more humanely, we can as well.