Source: Michigan News

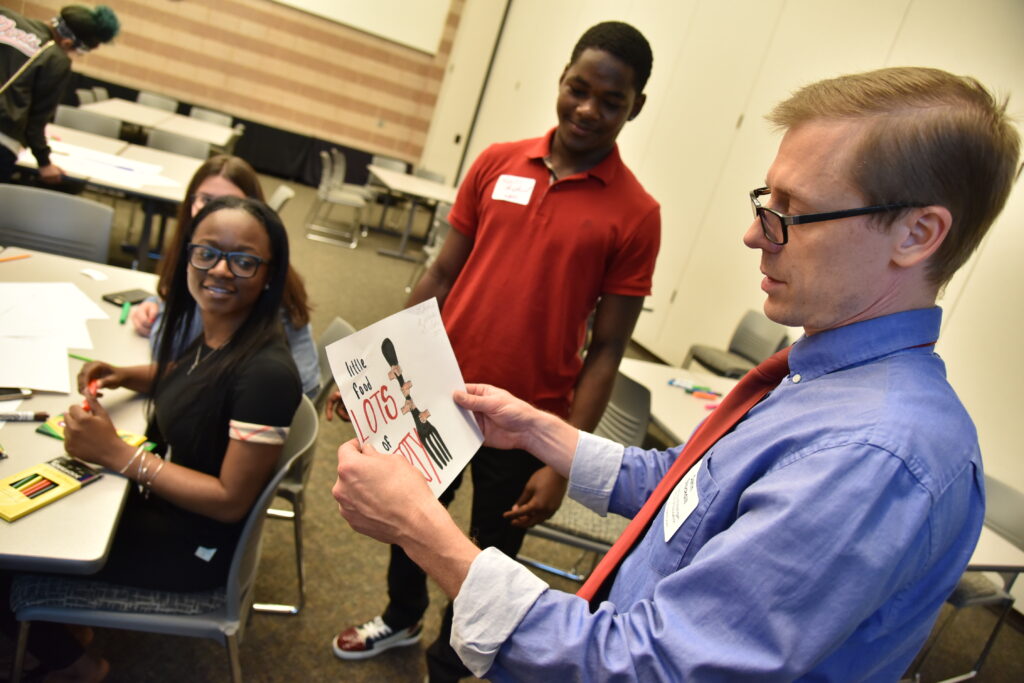

Darin Stockdill, right, meets with students at Waterford in a program with Oakland Schools called the Equitable Futures Youth Forum.

Darin Stockdill, right, meets with students at Waterford in a program with Oakland Schools called the Equitable Futures Youth Forum.

Darin Stockdill’s work with Detroit youth at a community center and as a middle and high school social studies and English teacher will certainly inform his current project.

As part of the larger Detroit River Story Lab project led by University of Michigan English professor David Porter, Stockdill will support history scholars and educators connected to the Detroit River Project and the Essex County Black Historical Research Society in Windsor, Ontario to develop curricular materials for middle school teachers in both Michigan and Ontario, Canada.

He’s the instructional and program design coordinator at the Center for Education Design, Evaluation, and Research at the School of Education.

Teachers on both sides of the border will be able to use the standards-aligned materials to engage their students with the transnational histories of the Underground Railroad and the key geographic role of the Detroit River. These lessons will tie this important legacy of Black resistance and anti-racist organizing to contemporary issues of racial justice and will introduce students to events and historical figures that have often been ignored in conventional curricula.

How might your experience teaching in Detroit inform this current work with the Detroit River Story Lab.

I first worked in Detroit starting in 1993 at Latino Family Services in southwest Detroit, where I was a youth worker for a few years. We would regularly take kids down to Riverside Park on the Detroit River, and that’s when I got to know the riverfront and started getting more engaged with the history of the city. Then I started teaching, and I ended up at a charter school in Detroit, Cesar Chavez Academy. I taught middle school social studies and English, and then when they added a high school, I was one of the first teacher leaders. I tried to connect community history and my students’ lived experiences to narratives of national history in my classroom, and I learned a lot in the process. Later, I entered graduate school at U-M and worked with (School of Education Dean) Elizabeth Moje on adolescent literacy research in Detroit schools. That experience of being a youth worker, a teacher, and then a researcher gave me insights that I still call on when I develop curriculum now.

The Detroit River. Credit: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

For example, there was this “aha” moment in a research project where we were gathering survey data on adolescent literacies from middle and high school students. We were asking them about their favorite classes, their least favorite classes, and what they liked to read, and we noticed this really interesting tension in their answers. A majority of students said that social studies was their least favorite class, about 720 out of around 1,000 kids. I was really disappointed as a social studies teacher, but not too surprised. Then when we asked them what they liked to read, they were talking about books like Night by Elie Wiesel; they listed a whole range of books with historical and cultural themes about the human experience, but weren’t engaged in the class that should have connected to these questions. So they found historical narrative engaging, but not history education, and this disconnect seemed to emerge from how history was being taught, and also from whose history was being taught.

So I ended up using my dissertation to explore how to use local historical issues to develop historical literacy and to get kids thinking more deeply about history by more clearly connecting it to their lives and to compelling stories. That work has carried over into my professional work around place-based and social justice oriented education.

And looking back to my experience as a teacher, I have a lot of empathy for teachers, especially now in the pandemic, and I try to design for teachers who are very busy and don’t have a lot of time to go find and adapt resources. In particular, I try to create materials that are comprehensive but also flexible so that teachers can mold them to their given context.

All of these experiences shape the way that I develop curriculum, and for this specific project, a place-based project, I’m thinking about the narratives that are really going to capture the imagination of young people and bring history to life for them, while also wanting to capture connections to current issues of racial justice, such as the role of the police in society.

These are really important issues for kids to learn about, but they’re not new issues, right? So in the 1800’s in Detroit, the role of law enforcement and the state in quite literally policing Black bodies was a key issue, and there was community organizing and resistance in Detroit as Black people, along with some White accomplices, fought to protect the Underground Railroad and prevent the Fugitive Slave Act from being enforced in Detroit. This is a historical legacy that many kids don’t learn about. In many schools in our state, students learn about the Underground Railroad as something that happened someplace else, or they might read one thing about what took place in Detroit, but don’t get the full picture that Detroit was this really pivotal place in the history of resistance to slavery. Similarly, when we teach about slavery, it often gets framed a southern experience, but slavery existed in Detroit and Michigan for many years in different forms. I think this project provides an exciting opportunity to engage kids with this history.

What would you say would be a good book for people to read about, about that history?

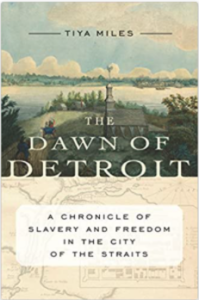

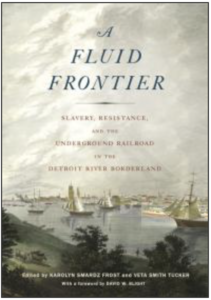

I’m reading it right now, The Dawn of Detroit, A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits, by Tiya Miles. Miles was at U-M for awhile and is now at Harvard, and is a prominent historian of slavery in Detroit. This is a beautifully written book presenting a really deep history of these issues. I should also recognize one of the key players in this project, Kimberly Simmons, director of the Detroit River Project, and the book she contributed to A Fluid Frontier.

I’m reading it right now, The Dawn of Detroit, A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits, by Tiya Miles. Miles was at U-M for awhile and is now at Harvard, and is a prominent historian of slavery in Detroit. This is a beautifully written book presenting a really deep history of these issues. I should also recognize one of the key players in this project, Kimberly Simmons, director of the Detroit River Project, and the book she contributed to A Fluid Frontier.

I won’t pretend to be a historical expert in this area, which is why I’m excited to be working with Kim Simmons, and also with Irene Moore-Davis, president of the Essex County Black Historical Research Society in Windsor. Perhaps the most exciting prospect for me is to learn from them because they have such deep, historical knowledge and connection to this work.

How did you get involved with the Detroit River Story Lab project?

I think the way it happened is that Kim Simmons and David Porter had been working together and learned about the School at Marygrove in Detroit, which is a School of Education collaboration with the Detroit Public Schools Community District. They were thinking that the School at Marygrove might be a great site for some of this work around the Underground Railroad and the Detroit River, and we connected through my involvement with the School at Marygrove. So it was basically through David and Kim’s collaboration and interest in finding an educational partner.

I think the way it happened is that Kim Simmons and David Porter had been working together and learned about the School at Marygrove in Detroit, which is a School of Education collaboration with the Detroit Public Schools Community District. They were thinking that the School at Marygrove might be a great site for some of this work around the Underground Railroad and the Detroit River, and we connected through my involvement with the School at Marygrove. So it was basically through David and Kim’s collaboration and interest in finding an educational partner.

What does the standard 8th-grade curriculum include and how is that not meeting the needs of this project?

One of the challenges of curriculum design, and this is where a center like CEDER becomes valuable for people, is figuring out which teachers and grade levels are most likely to use a resource set. You might design curriculum around the Underground Railroad and try to get it into high school classrooms, but high school US history teachers in Michigan generally just do a brief review of that because they’re supposed to teach from Reconstruction all the way up until today, whereas 5th and 8th grade US history teachers have state content expectations that cover slavery and resistance to slavery. So with this project we’re going to focus on 8th grade in Michigan, and also on 7th grade in Ontario, as their curriculum content lines up a little bit differently.

And what’s missing from the current, conventional 8th-grade curriculum are place-based and social justice components, especially for African-American children in a city like Detroit. Education research into curricula has shown that youth of color, particularly Black youth, often don’t feel represented in or connected to traditional textbook driven curricula. There’s a lack of representation, and there’s certainly a lack of discussion of resistance and community organizing. Teachers are left to develop that on their own if they want.

There’s generally coverage of the Underground Railroad, often focused on Harriet Tubman, but it can be quite limited. So we hope to present more compelling materials with personal and community stories from this region. Another piece that is usually missing is the role that Canada, and Black Canadians, played in this story. I’m learning a lot about this history from Shantelle Browning-Morgan, who is a teacher in Essex County, Ontario and is guiding a lot of the design work for this project. She is deeply knowledgeable about the history of Black Canadians, and was teaching me about back-and-forth migration across the Detroit River. Although Canada is often presented as the land of freedom in discussion of the Underground Railroad, many people who had escaped slavery to Canada chose to return to the United States when slavery ended in 1865 as they were facing a lot of racism in Canada. So we want to present a more honest historical narrative and illustrate how Black people moved in both directions across the river and border in their freedom seeking.

This idea of place-based education is to connect what students learn about history to their communities and lived experiences so that they better understand the way that their community has both impacted history and been impacted by history. There’s a reciprocal relationship with larger spaces… their community is part of a national narrative, and they can join that process. Detroit was really important in resistance to slavery and we feel like it’s powerful for young people to be able to see their city and their community as having a place in history, to see themselves represented, and to understand that they can be part of a long legacy of struggling for justice.

They can also go visit some of the key sites, at least once we’re out of pandemic mode. For example, we envision a time when students will be able to go to the Detroit riverfront and stand by the Gateway to Freedom statue at Hart Plaza and look out across the river while reading an historical account. Or they could stand there and have Kim Simmons tell a story about her own family’s experience. We want to build these place-based opportunities where kids can actually be in a historical location as they’re learning about it, and bring the city’s history to life for them, bringing their own community into the historical narrative in a way that doesn’t happen when they’re just learning about it in the abstract.

I guess it’s another discussion of why that isn’t happening already, but do you have any insight there?

I wouldn’t say that this kind of education doesn’t happen at all. There are wonderful teachers who are already doing this work in Detroit and other communities, as well as amazing local historians working with youth. It happens in pockets, and one of the reasons why it doesn’t happen more is that developing these resources takes a lot of time and expertise. You need a project like this where we have the deep, historical expertise of Kim and Irene; we have somebody like David Porter who’s helping to organize it, connecting people across the university, and we have myself and Shantelle Browning-Morgan focusing on the educational design. Teachers, and school district curriculum leaders as well, are often operating to solve day to day challenges, especially now in the pandemic, and generally don’t have the time or the resources to develop something like this.

I wouldn’t say that this kind of education doesn’t happen at all. There are wonderful teachers who are already doing this work in Detroit and other communities, as well as amazing local historians working with youth. It happens in pockets, and one of the reasons why it doesn’t happen more is that developing these resources takes a lot of time and expertise. You need a project like this where we have the deep, historical expertise of Kim and Irene; we have somebody like David Porter who’s helping to organize it, connecting people across the university, and we have myself and Shantelle Browning-Morgan focusing on the educational design. Teachers, and school district curriculum leaders as well, are often operating to solve day to day challenges, especially now in the pandemic, and generally don’t have the time or the resources to develop something like this.

My last question is what do you hope would be the takeaway for students who are learning this curriculum, probably and learning these kinds of stories for the first time?

That their communities, particularly for kids in Detroit and Windsor, but even in southeast Michigan and Ontario, played really important roles in the fight against slavery and white supremacy. I want them to see and understand that communities organizing for social justice and freedom have been part of this area’s history for a very long time.

The other thing we want students to learn, and this is central to the work of the historian Tiya Miles, is that slavery is a part of the history of Detroit and Ontario. It’s not just this terrible thing that happened in the U.S. South. Both nations were shaped by slavery and there were enslaved people living in Detroit, as well as free African-Americans, who actively resisted. Their stories of survival and resistance are important, and we can learn from them and be inspired today, on both sides of the river.