Source: Michigan News

Chandra McDuffie, supervisor at Green Industries, says the great thing about the coasters and other manufacturing processes is that it helps build confidence for people who are entering or rejoining the workforce.

The original glass coasters launched in 2012 feature murals from Detroit’s “Wailing Wall” near Eight Mile Road and Wyoming that was built in 1940 as a division between Black and white neighborhoods. The images of brightly colored houses, factories and neighbors added years later gave the wall new meaning.

Credit: Eric Bronson, Michigan Photography

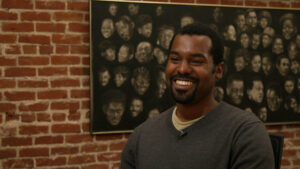

Brandon Carmichael came to Green Industries without a lot of work experience, but now has manufacturing know-how thanks to a product University of Michigan students designed to help homeless men and those with disabilities learn valuable job skills.

Carmichael makes boxes from wood reclaimed from Detroit houses in a multistep process that hold coasters made from recycled glass.

Brandon Carmichael gained valuable job skills making boxes from reclaimed wood at Green Industries.

“This program has taught me everything that I really wanted to do. I mean, it’s a challenge,” he said. “My skills that I learned there, yes, I can go somewhere else and work.”

The coaster minibusiness grew from a U-M course that brought together students of business, engineering and art and design. The class worked closely with Cass Community Social Services, a Detroit-based nonprofit dedicated to providing food, housing, health services and job programs, to brainstorm and set up the business.

The original glass coasters feature murals from “Detroit’s Wailing Wall” near 8 Mile Road and Wyoming that was built in 1940 as a division between Black and white neighborhoods. The images of brightly colored houses, factories and neighbors added years later gave the wall new meaning.

“We fell in love with the imagery … and particularly attractive was the narrative arc here because the wall was built to divide us. And we’re going to take the image from that wall on a project that brings us together, serving some of the very same people that wall was meant to disadvantage,” said Bill Lovejoy, the Raymond T.J. Perring Family Professor of Business Administration at the U-M Stephen M. Ross School of Business.

Coaster display at Cass Community Social Services in Detroit.

“So coming full circle, I thought there was a very powerful story behind the coasters. You’re talking about a wall that allows one group of people to invest in their property so that there’s some equity to pass on to their kids who benefit from that. And the other half on the other side of that wall, they can’t do that,” said Lovejoy, who received the Spirit of the City of Detroit award from the Detroit City Council in 2018.

Lovejoy challenged his students to use materials that would otherwise enter the waste stream. So they took tours of vacant lots in Detroit and found rubber, glass and wood in good quantities. There was very little metal because that’s being salvaged. Then they brainstormed what they could design with the materials.

The students installed the production equipment at Cass in 2012 and set about teaching homeless men how to use it. Since then, thousands of coasters have been produced at Green Industries, which also creates mud mats from abandoned tires and pays developmentally disabled adults to shred documents for recycling.

Detail of coaster boxes made from wood reclaimed from demolished Detroit homes.

Workers can put 50 coasters in the kiln at a time. It takes 24 hours to fire them and then cool them down. As work progressed, the men started taking control of the process and suggesting ways to solve problems and make a better product. They’ve since added coasters with images of iconic Detroit buildings, inspirational leaders quotes for African American History Month and a series on Cass’ Tiny Homes initiative.

And, Lovejoy said, it’s an example of the university making a positive difference in the world without fanfare. It’s about doing the smaller things that change people’s lives. The men now have a purpose to get up in the morning and go to work. They make a little money and can treat a friend to dinner or buy a birthday gift for someone close to them.

And now, they are just trying to keep up with demand for the coasters, which sell for $25 for a set of four, said the Rev. Faith Fowler, executive director for Cass Community Social Services and an adjunct professor at U-M’s Dearborn campus.

Finding jobs for homeless men has been difficult, she said, but making the coasters has given them a chance to be creative, make some money and be part of a group. Green Industries employs 83 homeless workers.

The Rev. Faith Fowler, executive director for Cass Community Social Services and an adjunct professor at U-M’s Dearborn campus, says the coasters have provided jobs for more than 80 homeless and developmentally disabled men.

“It’s been a great product,” Fowler said.

Green Industries, a division of Cass Community Social Services, started in 2007 during the housing crisis when jobs were hard to find. They started with recovering illegally dumped tires from which they made mud mats.

“All of it’s tied to the environment, because poor people are hit first and worst by pollution, degradation of the planet,” Fowler said. “We’ve tried to create jobs that will have more than one function. We’ll clean up the air and the land and the water, and allow people to have jobs that can’t be outsourced, and potentially a living wage.”

Onye Ahanotu

Onye Ahanotu, who graduated from U-M in 2012 with a master’s degree in materials science engineering and was part of the original student team, said the project was as “real world” as you get in college. While the team started with a glass garden planter, production issues made that difficult to sustain so they went with the glass coasters.

“We came up with an idea. That idea could have ended there, which at many schools I feel like it does end there,” Ahanotu said. “But we continued, we actually implemented a real process, and I think that’s the really unique part about the University of Michigan.”

Chandra McDuffie, supervisor at Green Industries, says the great thing about the coasters and other manufacturing processes is that it helps build confidence for people like Carmichael. He started off as a developmentally disable client and developed skills in making the coasters and coaster boxes. And now he’s a full-time employee.

Chandra McDuffie, supervisor at Green Industries, says the great thing about the coasters and other manufacturing processes is that it helps build confidence for people who are entering or rejoining the workforce.

“Some people don’t have skills. You teach them how to do something. They have a job. So they’d be able to move forward in the workforce,” McDuffie said. “You can be working here, making coasters one day and working at Ford the next. You never know who is going to come in and be a contact and help you to better yourself.”

The coasters business “is a wonderful thing because it’s giving jobs back and it’s recycling because we got one planet. So if we recycle stuff, we maybe can be here a little bit longer,” she said.