University of Michigan researchers are monitoring Detroit’s vegetation from space to understand its connection to urban decline — and gaining insights into a public health threat emanating from the city’s vacant lots.

As part of the Detroit School lecture series, Daniel Katz and K. Arthur Endsley last week described their use of satellite imagery to investigate changing patterns of urban vegetation and what it might reveal about localized socio-economic conditions.

The use of satellite technology for this purpose is relatively new but its output – constantly updated, high quality data that document changes to the natural and built environment over decades – is potentially powerful.

Detroit’s stark population decline since the middle of the 20th century has led to extensive demolition and an estimated 90,000 vacant lots that are home to expansive plant life.

Endsley, a doctoral fellow and Ph.D. candidate in the School for Environment and Sustainability, uses remote sensing to explore vegetative growth in declining neighborhoods and assess how it correlates with housing values, foreclosures, abandonment, demolition and other factors. He has found a strong association between increased vegetation in Detroit and residential stability, racial segregation and the economic disenfranchisement of minorities.

Katz, a post-doctoral fellow in the School of Public Health, notes that unrestrained vegetation on Detroit’s vast sections of vacant and abandoned property creates safety and visibility concerns, exacerbates dumping, and produces excessive pollen that causes allergies and asthma.

Asthma is more prevalent in Detroit than in Michigan as a whole and disproportionately affects black residents, according to the state Department of Health & Human Services. It is the leading cause of preventable hospitalizations among children in Detroit.

“It’s not just a nuisance,” Katz said. “Pollen in Detroit is a big deal. It’s incredibly prevalent.”

A particularly notorious source of pollen – ragweed – thrives in vacant lots.

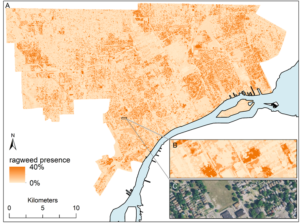

Katz uses field surveys and data collected by satellites to map ragweed across the city and gauge the volume, timing and dispersion of pollen.

“This is challenging,” he says. “Detroit is enormous.”

In later phases of this research, Katz hopes to conduct epidemiological analyses to better understand the health impact of excessive pollen produced on Detroit’s vacant land. This disproportionately affects people in poor neighborhoods, he notes, where access to medical care is limited and asthma often goes untreated.

David Wilkins is an Ann Arbor-based freelancer with more than 20 years of experience in corporate communications and journalism.