Source: Taubman College

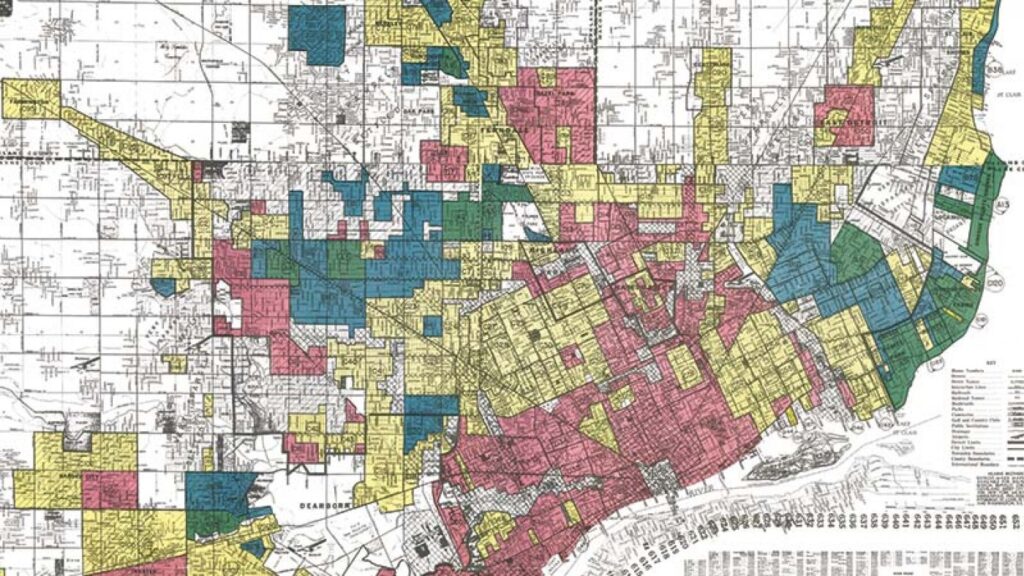

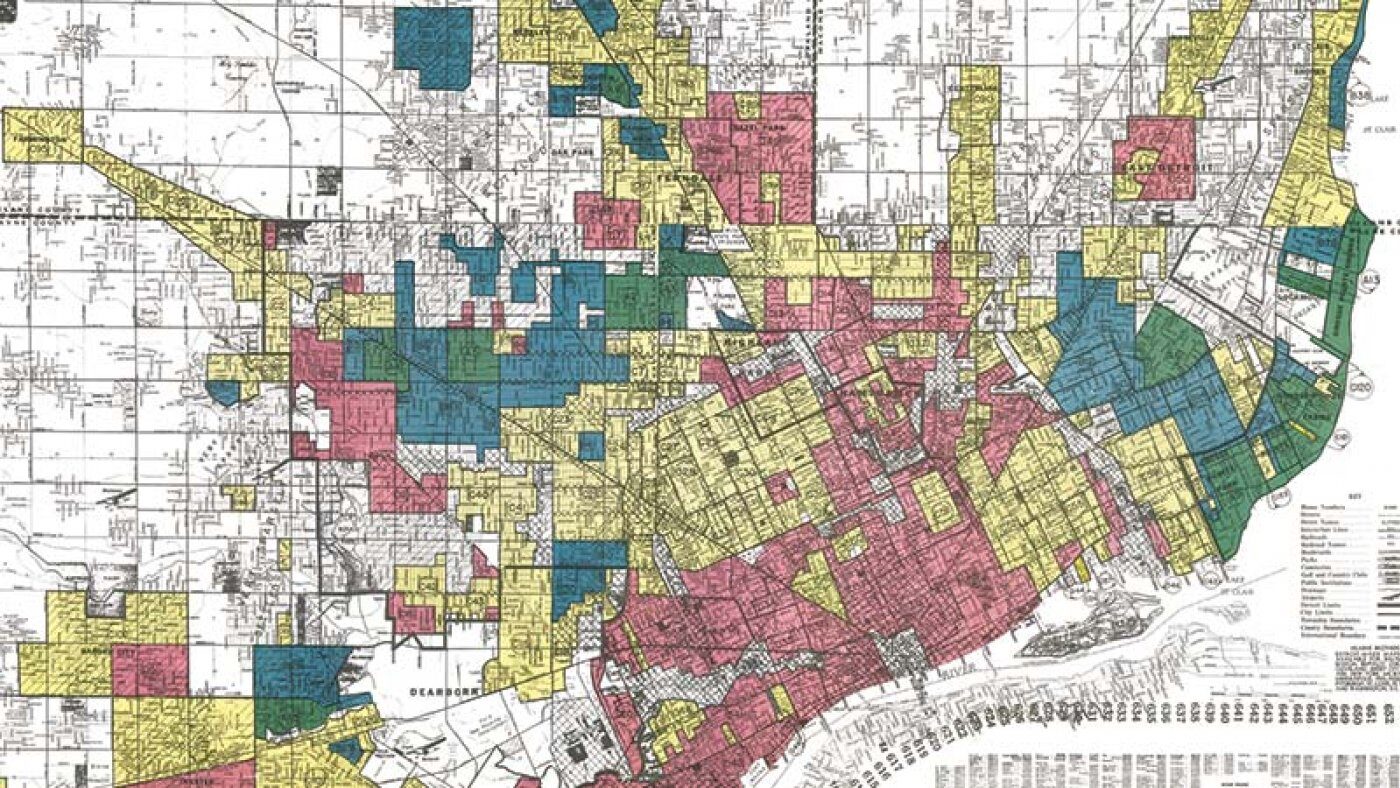

Eight Mile Road marks the border between the city of Detroit and the suburbs of Oakland County. But this multilane thoroughfare, which carries traffic past sprawling shopping plazas and neighborhoods of modest single-family homes built during the prosperous years after World War II, represents more than a geographic boundary. It’s also a stark line between a Black city and its white suburbs, between a community with a median household income that hovers around half the national average and one of the wealthiest counties in the United States.

“When you see it on a map, you start to see how people in Detroit really lost out on building wealth,” says Larissa Larsen, associate professor and chair of Taubman College’s urban and regional planning program.

Detroit is an extreme example, but nationwide Black families still have about a 10th the wealth, on average, of their white counterparts, primarily because of a gap in rates of home ownership. “Certainly there’s structural racism baked right in there,” Larsen says. “And we, as architects and planners, worked for a century building American cities — so we’ve participated in making that happen.”

History shapes cities in myriad ways: through deliberate planning and government policy, the rise and fall of industries, war, disaster, and migration. The ways in which urban denizens are displaced, segregated, and cut off from resources today are also rooted in the past, and rectifying these inequities requires untangling those legacies.

That need is at the heart of an emerging field of research known as urban humanities, which at Taubman College has centered on a grant program called the Michigan-Mellon Project on the Egalitarian Metropolis. First funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in 2013, the Egalitarian Metropolis was led since 2017 by Taubman College’s Robert Fishman, who retired in June as a professor of architecture and urban and regional planning, and by Angela Dillard, the Richard A. Meisler Collegiate Professor of Afroamerican and African Studies and current chair of the history department at the College of Literature, Science and the Arts.

Now in its concluding year, the project is evolving into an Urban Humanities Initiative at the University of Michigan, which will continue to connect humanities researchers, planners, and architects, along with community leaders outside the university, as they work toward a fairer future.

Robert Fishman grew up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, a train ride away from Manhattan, where the strata of history can often be found close to the surface.

“I was one of the bridge-and-tunnel people, as they’re called,” he says with a laugh. “For us, New York was even more of an ideal and a revelation than it was for the people who were actually living within the city — I keep coming back to New York as my archetypal metropolis.” As a teenager in the 1960s, Fishman took frequent trips into the city, spending long hours exploring its renowned art museums. But he also became fascinated by New York itself and by the extremes of wealth and poverty that were often on display.

His curiosity led him to The City in History, a now-classic book by the historian Lewis Mumford, first published when Fishman was in high school. Mumford’s lyrical study of how the Western urban form has changed over time — from the ancient Greek city-states and cathedral towns in medieval Europe to the modern capitalist metropolis — would prove a lifelong influence.

“I’ve assigned it in literally every course I’ve ever taught,” Fishman says. “Mumford’s way of looking at the city, his deep understanding of the impact of culture, has certainly shaped my work more than anyone else.”

Fishman went on to study history in college and graduate school, spending the first half of his teaching career in traditional history departments. When he came to the college in 2000, recruited as part of a new master’s program in urban design, he found a student population eager to incorporate historical context into the study of design and planning.

“To be an urban designer, you really have to love the city, which means trying to grasp what is unique about each city,” Fishman explains, “and to understand what is unique about it you really have to look into the past, into the urban biography that has shaped every city.”

Fishman was part of the original team of faculty and students, led by Taubman College Associate Dean Milton Curry, who won the six-year, $1.3 million grant for the Michigan-Mellon Project on the Egalitarian Metropolis. Initially the project compared three cities — Detroit, Rio de Janeiro, and Mexico City — through a framework that assumed the inherent worth and equality of all the people who called each home. What were the most challenging contemporary issues facing these different communities, they asked, and how did their causes and solutions connect to history, economic and political forces, architecture, and urban design? The wide-ranging effort resulted in a series of courses, exhibitions, and symposia, which brought together academics with community leaders from the cities themselves.

In 2019, a second, $1 million grant allowed the project team to take a deeper look at a single city: Detroit, which — more than almost any other in the United States — has seen its fortunes rise and fall on the tide of larger historical forces. After Curry’s departure to be dean of architecture at USC, the project was now jointly headed by Fishman and LSA historian Angela Dillard. Fishman couldn’t imagine the Project without this close collaboration. “I’m something of an outsider to Detroit. Angela grew up as a Black Detroiter, daughter of a prominent clergyman, and someone whose life and scholarship have been deeply engaged with Detroit. She brings a perspective that I couldn’t alone.”

Read the full story here.