Nick Tobier, a professor at the University of Michigan Stamps School of Art & Design, rides the Detroit People Mover near the Detroit River. He wrote the book “Looping Detroit: A People Mover Travelogue.” Photo: Daryl Marshke, Michigan Photography.

Nick Tobier has spent a lot of time on the Detroit People Mover. Teaching, exploring, observing, escaping.

On a rare sunny day in February, sandwiched between snow and ice storms, we boarded the city’s iconic monorail together at the Grand Circus Park station, just outside the David Whitney building. Tobier happily paid my 75 cent fare (he prefers buying the tokens — “I feel good when I have them in my pocket,” he says) and led me up the escalator to the platform.

As we ride, Tobier, a professor of art and design in the Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design at the University of Michigan, notices, and notes on, nearly everything. Once-empty storefronts full of tech workers; a big hole in the ground where the Hudson’s building had been; retro-futuristic walkways that connect parking garages to Joe Louis Arena; Windsor’s nondescript skyline across the gray Detroit River; small businesses not yet paved over for surface parking.

Tobier grew up riding the subway in his native New York. He remembers first seeing the People Mover in the ’80s sci-fi action movie Robocop (the movie was released the year the People Mover launched). By the time he moved to this area in 2003, he was aware of its conflicted backstory and critique as an expensive public transit flop. It didn’t take him long to fall in love with it anyway.

“I was ready to approach it ironically, but I really have genuine affection for it, just because you have this amazing view,” he says.

When we get off at the Greektown stop, Tobier’s still observing, stopping to talk with security workers, casino patrons, and the chauffeur of a new autonomous electric cab service. He points out the architecture of the Wayne County building and the white terra-cotta exterior of the Cadillac Tower (“unique to Detroit, Paris, and parts of Brooklyn”).

Tobier is simultaneously warm about and distracted by his love for the city surrounding us, and his enthusiasm for this “sweet little train” and the area it circles is contagious. A few winters ago, he spent several days a week wandering downtown, stopping into old bars and riding the People Mover — sometimes for hours at a time — to warm up.

View from the Detroit People Mover of Jacoby’s in Greektown and the GM Renaissance Center in the background. Photo: Daryl Marshke, Michigan Photography.

“My whole world was circumscribed by this little loop here,” he says. “Just snowy and cold and kind of atmospheric.”

Tobier’s work is focused on civic engagement, and he often brings U-M students together with Detroit school groups in grades 4 through 12 for day trips like this downtown to observe, sketch, and get ideas for projects that “make some kind of impact.” Previous projects include designing solar bike lights from discarded Gatorade bottles and a screen printing business run by high school students.

His main work currently is with the Brightmoor Makerspace, a former Ford garage that’s been converted into a into a workshop geared toward youth development for making things.

On windy days, Tobier says fourth graders on the People Mover almost always point out the birds flying backwards over the river. More recently, they’ve been noticing “all the white people.”

“It didn’t used to be that way in the heart of Detroit,” he says. “The high school students call this ‘white town.'”

As we continue walking, Tobier points out all the People Mover stops and trains circling us. Within its 3-mile route, you’re never far from either. But after all these years, it hasn’t morphed into background for him.

“I’m totally always aware of it,” Tobier says. “The rumble it makes when it’s coming. I love the sound.”

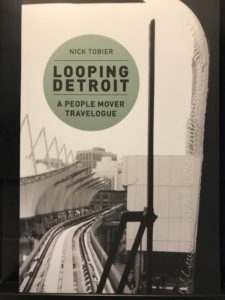

Years ago, Tobier had the idea to ask other “explorer” types — artists, writers, etc. — to choose one of the People Mover’s 13 stops, spend some time there, and write something about it. He then compiled those entries into the book “Looping Detroit: A People Mover Travelogue,” (University of Michigan Press, 2016). It’s a quick read with several different takes on the assignment and lots of beautiful black and white photos by Tobier.

Originally conceived as a study in Detroit’s under-celebrated architecture and the “shape of the city,” Tobier was surprised by how political, personal, and moving some of the contributions were.

Since the original release push, Tobier says the book’s best sales come from museum gift stores and art and architecture bookshops overseas (“Europeans are fascinated with Detroit”). He’s dreamed of hosting some kind of event on the train and at each stop for years now, though. Something that would include readings from each author and some kind of performance.

When asked about his own favorite spots inside the People Mover’s orbit, Tobier says: “It’s somewhere between the Detroiter Bar and the lobby of the Guardian Building.”

The ambiguity of this statement amuses me, since we’ve just walked the literal distance between these two — one a nondescript Bricktown bar, the other an awe-inspiring art-deco landmark — and Tobier has noted many of the sites we pass in between. But he clarifies quickly: “I like both of them equally but for different reasons.”

The Grand Circus Park stop of the Detroit People Mover overlooks Woodward Avenue. Photo: Daryl Marshke, Michigan Photography.

After reboarding the People Mover, we make another loop and a half and return to Grand Circus Park. Saying our goodbyes, Tobier gives me a token to take with me as we part.