Source: Michigan Impact

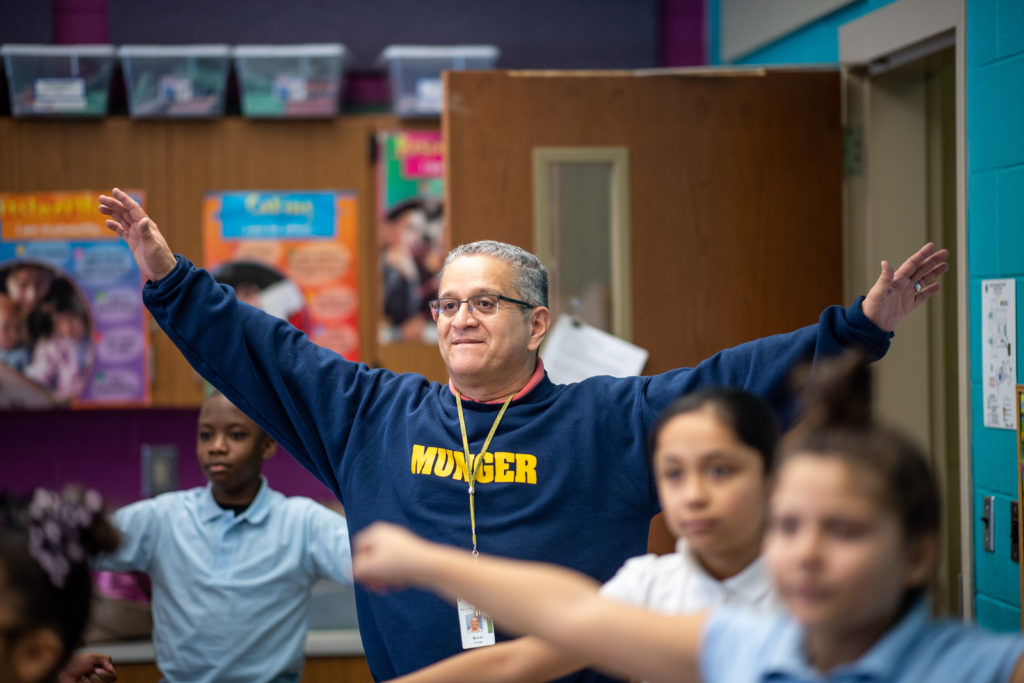

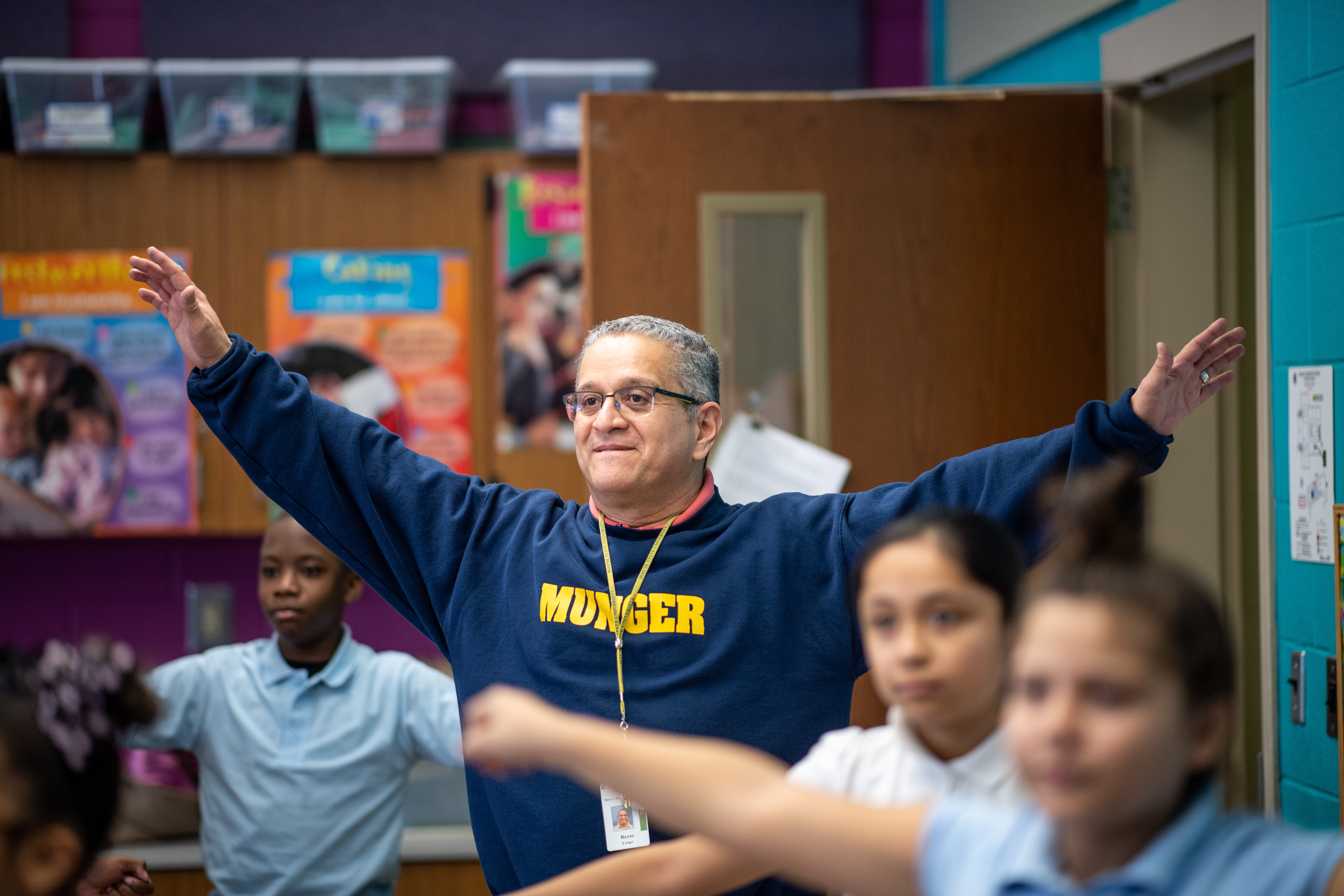

“The kids were the ones reminding me: ‘Hey Mr. Reyes, it’s time to dance!’”

Among the many things that years of teaching elementary school students has taught Cesar Reyes, is that kids sit too much during school and should move more.

More Info

Studies:

- Acute compensatory responses to interrupting prolonged sitting with intermittent activity in preadolescent children

- The effects of interrupting prolonged sitting with intermittent activity on appetite sensations and subsequent food intake in preadolescent children

- Affective responses to intermittent physical activity in normal weight and overweight/obese elementary school-age children

- Acute effect of computer-game and exercise breaks on math performance in preadolescent children

- Feasibility of inPACT intervention to enhance movement and learning in the classroom

So when Reyes, a teacher at Detroit’s Munger Elementary-Middle School, was asked to try an in-class exercise program developed at the University of Michigan, he was all for it.

The program, called InPACT (Interrupting Prolonged sitting with ACTivity), incorporates five bursts of moderate-to-high-intensity exercise into the class day, for a total of 20 minutes. It’s led by Rebecca Hasson, U-M associate professor of kinesiology and nutritional sciences, and was developed with the U-M schools of public health, education, and architecture and urban planning, and Project Healthy Schools.

Rebecca Hasson

Hasson is director of the Childhood Health Disparities Research Laboratory, and much of her research focuses on finding ways to incorporate exercise into children’s lives to curb the growing pediatric obesity epidemic. The lab’s research showed that uninterrupted prolonged sitting is associated with increased disruptive behavior and lower academic achievement in addition to increased obesity risk.

With cuts to budgets and more time spent on standardized testing, physical activities and physical education are being squeezed out of the school day. InPACT brings activity back.

Munger is the latest school to bring the lab’s research into the classroom. Columbia Elementary in Brooklyn, Michigan; Estabrook Learning Center in Ypsilanti; and Jesse L. Anderson Elementary in Trenton came before Munger.

“Pediatric obesity has more than tripled over the last 30 to 40 years, and this is particularly true in minority youth,” she said.

Sitting and lack of physical activity are big contributors, and while 20 minutes of exercise doesn’t seem like much, consider that physical activity is being engineered out of many schools, Hasson said.

“We’re trying to create a culture of health throughout the entire school day, not just in gym.”

Rebecca Hasson

As childhood obesity rates rise and physical education offerings dwindle, elementary schools keep searching for ways to incorporate the federally recommended half-hour of physical activity into the school day, she said. Kids are supposed to get an hour of exercise a day—30 minutes of that during school. Most don’t.

Munger Elementary/Middle School in Detroit

“Many kids don’t have PE every day but they might have recess, and if they get 10 more minutes of activity there, it would meet that school requirement,” Hasson said. “This doesn’t replace PE, it’s a supplement. We’re trying to create a culture of health throughout the entire school day, not just in the gym.”

The obesity epidemic is particularly harmful for children because they’re living with excess fat longer than ever before, she said.

To develop the program, Hasson’s lab first partnered with U-M’s College of Architecture and Urban Planning, which redesigned classroom setup and furniture to promote activity. Researchers then tested the program in the lab, and this portion of the intervention was called Active Class Space––basically the pre-testing for the classroom intervention.

Physical activity helps the kids focus on classroom learning

Researchers tweaked the program along the way, trying exercise breaks of two, three and four minutes, and developing ways to make the exercise more enjoyable for students and more feasible for teachers.

The initial findings were positive: Unlike adults, the kids in the study who did 40 minutes a day didn’t eat back the burned calories or become couch potatoes when they got home. Children burned an additional 150 calories a day, and considering one pound is 3,500 calories, that adds up over time.

The exercise breaks didn’t disrupt learning, and 99 percent of the kids were able to resume book work within one minute, Hasson said.

Ben Ransier

Eventually, the U-M team was ready to test the program more widely in actual school settings, and that’s when Project Healthy Schools became involved.

Project Healthy Schools is a Michigan Medicine program that provides health education in 100 Michigan schools, one in Arizona and four schools in Bangladesh. Its focus is combating obesity in children.

Like Reyes, Ben Rainsier, curriculum and training coordinator for Project Healthy Schools, has long known that kids sit too much. When Rainsier read about the Active Class Space study in the campus newspaper, he knew right away he wanted to be a part of it.

“I reached out to Dr. Hasson and said, ‘This is awesome but this doesn’t deserve to be in a lab, this deserves to be in schools,’” he said.

The InPACT approach can help kids burn an extra 70-100 calories a day

With the help of Project Healthy Schools, the lab at U-M has worked with about 1,000 students and 29 teachers in four schools. Hasson hopes to secure funding to help implement InPACT statewide.

Reyes said that students seem less sluggish, happier and more engaged, and they looked forward to the exercise breaks. And, he said, students in urban districts like Munger are exposed to many stressors that can be eased by exercise.

Shortly after starting InPACT, the kids were reminding Reyes when it was “time to dance.”

“They love dancing, they love to move,” he said. “We were able to do the 20-minute workouts almost every day.”