Source: Michigan Medicine

Photos By: Eric Bronson, Michigan Photography

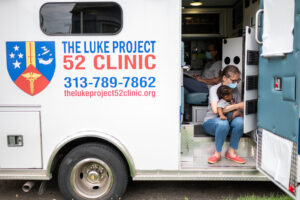

Sundance Gambino

“They care about you,” says Heavenlee Gordon, a patient of Luke Clinic

For mom Heavenlee Gordon, The Luke Clinic couldn’t have come into her life at a better time. At a church in southwest Detroit, Gordon found the help she needed and an added bonus: The doctors and nurses treated her like part of their own families.

“They care about you. They love you. They love your kids. And they make sure you’re OK, and even in the middle of the night, they answer their phones for you and just make sure you’re doing the right things with parenting and things like that,” said Gordon, a patient who had two children with the help of The Luke Clinic. “The other doctors didn’t do that for me.”

The Luke Clinic provides free prenatal, postpartum and infant care (through one year of life) to any family in the Detroit metro area. So far, it has seen more than 300 patients.

Even though most of the clinic’s patients have extremely high levels of medical, social and behavioral risk factors, they have shown lower rates of preterm delivery than the city of Detroit, which takes into account patients with health insurance.

“Our preterm delivery rate is about 10.4 per 1,000 live births, compared with 14.3 per 1,000 live births in Detroit,” said Katherine Gold, associate professor of family medicine at Michigan Medicine. “We also have lower rates of low birth weight infants, 6.2 per 1,000 live births compared with 14.6 for Detroit. We are proud of the care we can provide these vulnerable families, as well as the diverse range of services we offer our patients.”

To address the high rates of infant mortality in Detroit alongside other health disparities, Brad Garrison, a pharmacist and reverend, founded The Luke Clinic with his wife, Sherie Garrison, a high-risk labor and delivery nurse at Michigan Medicine.

Luke Clinic medical director Katherine Gold and co-founders Brad and Sherie Garrison, the executive director and clinical care coordinator, respectively.

“We lost a grandson who was stillborn, and we began looking at the issue of why babies die before their first birthday in the state of Michigan,” said Brad Garrison, who now serves as the clinic’s executive director, while Sherie serves as the clinical care coordinator.

“The number one reason that we learned in our research and studies was that it’s a lack of prenatal care,” Sherie Garrison said.

Gold, who serves as the clinic’s medical director and has since its opening in 2016, said the clinic is open twice a month and patients can access other free services around a variety of things including social work, insurance navigation, child care, breastfeeding support and language interpretation.

In 2019, Michigan Medicine’s Department of Family Medicine partnered with The Luke Clinic to provide services from four physicians on a monthly basis to help staff clinic hours. The department’s residents now rotate at the clinic and many of their patients choose to deliver their babies at Michigan Medicine’s Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospital, therefore increasing their continuity of care.

“Our partnership with The Luke Clinic is quite significant,” Gold said. “Michigan Medicine obstetrician-gynecologist Dr. Carrie Louise Bell serves on the clinic’s board of directors and two of our maternal-fetal medicine physicians offer consultations to high risk patients.”

Unlike many other clinics, Luke Clinic remained open during the pandemic.

Gold said that numerous nurses, nurse-midwives and administrative staff from Michigan Medicine also volunteer at the clinic, as well as Michigan Medicine C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital pediatrician Adrienne Musci.

Through this collaborative approach, Sundance Gambino, a patient at The Luke Clinic adds that the team truly elevates patient-centric prenatal, postpartum and infant care.

“They get in depth of who you are, how your body is, and what you personally need to have a healthy pregnancy and a healthy baby,” she said.

When it comes to accessing health care in the United States, deep-seated disparities among marginalized populations continue to exist. And while there are nearly 1,400 free clinics throughout the country to help offset these inequities, the uninsured and underinsured continue to struggle with obtaining the care they so often need. And just 7% of these clinics offer prenatal and obstetrical services.

“As you can imagine, many women of color report experiencing racial disparities and marginalization in their daily lives, but also while receiving health care, which often leads to a significant distrust of the health care system, overall,” Gold said. “Immigrants are sometimes fearful of deportation or being denied a green card and may choose to avoid care entirely, while mortality rates for Black and Hispanic infants are significantly higher than those of their white counterparts.”

“The mobile clinic became a lifeline for many patients” during the pandemic, says Katherine Gold.

Many of The Luke Clinic’s high-risk patients possess medical and social risk factors that contribute to struggles with mental illness and substance abuse. And many of these individuals found themselves without care at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“When the coronavirus hit, we were receiving multiple calls a week from people who were reporting that other Detroit clinics were closed to new prenatal patients,” Gold said. “We also lost access to most of our onsite support services, including the Detroit Health Department’s immunization services, our social work staff, insurance navigators, doulas and lactation consultants.”

Gold said that while the unexpected pandemic led to huge gaps in care and social support for these vulnerable families, in February, the clinic received funding from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan to test an outreach vehicle for antenatal testing and newborn care.

“This newly funded vehicle has become a lifeline for many patients in Detroit during the time of COVID-19,” she said. “The mobile care unit has been particularly helpful since the pandemic started due to our own service reductions.”

Gold noted that the mobile unit typically sees three to five patients per day, once a week. Staff drive to a patient’s home or workplace for testing, prenatal care, postpartum check-ups and newborn care. Typically, they have two nurses, an ultrasonographer and a driver on staff.

“More recently, I’ve been able to provide video visits to our clinic team and patients, reviewing fetal heart monitoring strips remotely, which allows me to participate in patient care,” Gold said. “We focus on our highest-risk moms for the visits, as many of them already have existing medical problems like diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity or advanced maternal age or teen pregnancy.”

Gold said that, sometimes, the clinic is the only place of respite for these patients.

“We have found that many of our patients have limited support from friends and family and may be in violent or abusive relationships with their partners,” she said. “Knowing that they can trust us helps provide some stability in their lives, as well as a place to turn to when they are scared or need resources.”