Source: Michigan News

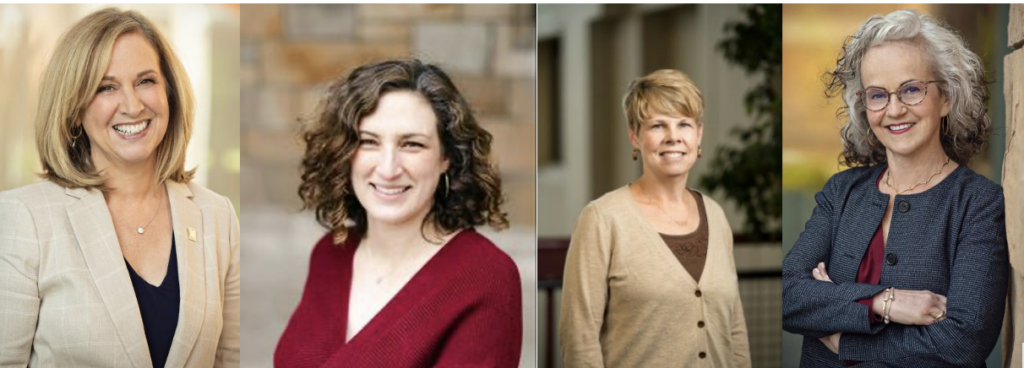

University of Michigan experts — including Elizabeth Birr Moje, Samantha Keppler, Pamela Davis-Kean and Deborah Loewenberg Ball — address key issues as students return to school.

Concept illustration of four children walking to school. Image credit: Nicole Smith, made with Midjourney

Back to school brings several challenges, from student learning, expectations of academic success and mental health concerns among children to questioning technology replacing educators and AI and the ongoing shortage of teachers, school staff and supplies.

University of Michigan experts can address these and other issues as students return to school.

Literacy, challenges and opportunities for schools, educators and students

Elizabeth Birr Moje is dean of the Marsal Family School of Education, the George Herbert Mead Collegiate Professor of Education and an Arthur F. Thurnau Professor of Literacy, Language, and Culture. Her research examines young people’s culture, identity, and literacy learning in and out of school in Detroit, where she leads Marsal Education’s participation in the P-20 Partnership and the Michigan Education Teaching School.

Elizabeth Birr Moje

“With the K-12 school year on the horizon, the discourse around learning is focused on ‘catching up’ as a result of the pandemic’s negative impacts on student learning,” she said. “Although it is true that average math and reading scores have declined across all groups, achievement scores are only a partial glimpse of what children are learning. More worrisome data show that children’s confidence in their abilities to engage in mathematics and reading has been shaken during the pandemic years. Educators need to focus on a wide range of learning outcomes to ensure that all students will be equipped to handle the demands of a new era.

“To that end, schools cannot fall back on the rote instruction in an attempt to ‘catch up.’ Educators should turn to evidence about how people learn best. And evidence shows that the best instruction engages children in real-world questions and problems as a way of learning foundational, critical thinking and team skills. Moreover, schools (not just teachers) need to address trauma and mental health challenges among children, even as they focus on improving skills.

“Finally, teachers will need support in learning to navigate rapidly emerging educational technologies and generative AI tools. Teachers need to learn how to advance children’s capacities for using such tools in everyday life so that the tools do not use them. These—and more—current realities demand historic investments to increase and retain well-prepared educators who are equipped to redress the challenges wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic and to meet the challenges of a new era.”

Contact: [email protected]

Samantha Keppler is an assistant professor of technology and operations at the Ross School of

Samantha Keppler

Business whose research derives insights about how to improve education operations or the management of human and material resources in public schools, educational nonprofits and edtech. She can talk about the importance of back-to-school supply requests that teachers post and when, how and why basic classroom materials matter.

“With so many big issues and concerns in education, school supplies can seem unimportant. That couldn’t be further from the truth,” she said. “Think about the microchip shortage in the car industry. Without these small tiny parts, the entire production system shut down. That’s what it’s like when teachers and classrooms lack the supplies and materials they need.”

Contact: [email protected]

Jean Mrachko

Jean Mrachko is the associate director of Michigan Alternate Route to Certification and accreditation and continuous improvement coordinator for the Educator Preparation Program. At M-ARC, she leads and manages all aspects of instruction in the program, from strategic planning and design to supervising staff and overseeing day-to-day operations.

Contact: [email protected]

Adjustments for children

Sandra Graham-Bermann

Sandra Graham-Bermann, professor of psychology, can discuss how parents can help their children cope with stress/time management as they return to school.

“We need to keep in mind that many children returning to school are struggling with mental health problems, with past traumatic experiences, or other adversities,” she said.

Contact: 734-615-7082, [email protected]

Pamela Davis-Kean

Pamela Davis-Kean, professor of psychology and research professor at the Institute for Social Research, has examined the various pathways that the socioeconomic status of parents relates to the cognitive/achievement outcomes (particularly mathematics) of their children. To help students navigate the pandemic’s impact on lower achievement scores, she recommends starting mentoring programs and creating individualized education plans for each student.

“Understanding the individualized instructional needs of each child is important as we continue to deal with the uneven educational experiences during the pandemic,” she said. “Students have been put back into grade levels with expectations of academic success when many of them missed the foundational training in the basic skills for reading and math.”

Contact: [email protected]

Jennifer Erb-Downward is a senior research associate at U-M’s Poverty Solutions who studies child and family homelessness. Her research explores the connections between student homelessness and school discipline rates, academic proficiency, graduation and dropout rates, chronic absenteeism, receipt of public assistance, and placement in the foster care system.

Jennifer Erb-Downward

“The start of the school year is a critical opportunity to identify students who may be experiencing housing instability and homelessness. These students have a right to additional educational support, such as transportation to school, which can prevent school absences and mid-year transfers that are known to negatively impact educational outcomes,” she said.

“The start of school also provides an opportunity for schools to ensure that eligible children are accessing benefits programs that can help to ease financial strain—such as SNAP food aid and Medicaid. Particularly, with pandemic era programs ending, this outreach by schools is needed to ensure that eligible children are not falling off of Medicaid rolls.”

Contact: [email protected]

Teaching practice

Deborah Loewenberg Ball is the William H. Payne Collegiate Professor of Education, research professor at the Institute for Social Research and director of TeachingWorks. Her research focuses on the practice of teaching, using elementary mathematics as a critical context for investigating the challenges of helping children develop understanding and agency and to work collectively, and on leveraging the power of teaching to disrupt patterns of racism, marginalization, and inequity. She is an expert on the demands of teaching and the imperatives for teachers’ professional education.

Deborah Loewenberg Ball

“In the aftermath of the pandemic, much has been made about learning loss—about students being behind—reinforcing foundational concepts of grade level as a standard for student progress,” she said. “What is missing is an acknowledgment of the obvious—that normal school was ruptured by the pandemic, making it virtually impossible for students to have learned at the same rate or been taught the same content. This leads to agitated moves to help students ‘catch up’ and assumptions that, because they didn’t learn to add fractions last year, they never will. This discourse relies on particular conceptions of learning and knowledge and its measurement, and neglects the social and emotional aspects of children’s growth and development.

“To address the needs of our young people and ensure their academic progress and their social development, it is vital that we attend to them as whole people who have had to adjust to a lot in the last three years. Our nation’s teachers are face to face with these multiple demands every day as they help children move forward. It has never been more important to support the work that teachers are doing and provide necessary resources and opportunities for professional learning.”

Contact: [email protected]

Instructional practices with technology

Liz Kolb, clinical associate professor of education technologies, can address how teachers can continue to use what they learned during remote and hybrid learning to teach using online methods.

Liz Kolb

“‘Will AI replace teachers?’ This question of technology replacing teachers is not new. In fact, it’s a question that has been asked since film strips came into the classrooms in the 1930s. And the answer has been the same for the last 100 years, no, technology will not and can not replace teachers,” she said. “Historically, we know that teachers do a lot of personalization and differentiation. While AI could summarize Shakespeare, AI cannot write about how Shakespeare’s play is relevant to an individual student’s everyday life because AI tools don’t know that student or their lived experience like a teacher does.

“Thus, every time there is a new technological innovation, we must stop asking if technology will replace teachers because history has spoken. Instead, we should ask how teachers can use this new technology to support their learners utilizing the science of learning. There are still things we do not know about technology and learning. Still, research over the last few decades has pointed to some clear areas that need to be present when technology is involved in learning, and they all involve a highly effective teacher. A few examples include teachers using sound pedagogical scaffolding techniques in conjunction with all technology tools and providing opportunities for students to be reflective when using the technology.”

Contact: 734-649-2563, [email protected]

Rebecca Quintana

Rebecca Quintana is the associate director of learning experience design at the Center for Academic Innovation and adjunct lecturer in educational studies. Her research centers on technology-enhanced teaching and learning, focusing on online and immersive learning environments within higher education contexts.

Contact: [email protected]