Surveillance from the air.*

In the fall of 2020, Josh Akers told me about the helicopters that had been continually circulating over his neighborhood in Detroit Seeing these images and hearing some of the pervasive sound created by the hovering blades made me think of Terror from the Air, by historian Peter Sloterdijk. Sloterdijk recounts that on 22 April 1915, in the midst of the First World War, French-Canadian troops in the northern Ypres were attacked using chlorine, the first instance of gas warfare in history. In that act, spreading terror in the air, modernity was born.

In Terror from the Air, by Peter Sloterdijk recounts that on 22 April 1915, in the midst of the First World War, French-Canadian troops in the northern Ypres were attacked using chlorine, the first instance of gas warfare in history. In that act, spreading terror in the air, modernity was born.

The gas attack was intended to deprive the French-Canadian troops of a milieu in which they could operate. The essence of Sloterdijk’s argument is that modernity is an assault on “givens”; it aims to question everything that is taken for granted…like breathable air… It is an attack on the environment, on what surrounds us, both real and conceptually. For Sloterdijk, that morning of 1915 announced the birth of both “atmo-terrorism,” and “environmental thinking.”

Sloterdijk points out what might be an essential aspect of terror: it is diffuse, pervasive, de-contained. Terror takes over the environment and over thinking. Could we hold the air? That would make breathing impossible. Think now of George Floyed–deprived of air, think of the continual roar of the helicopters overhead, depriving you of sleep, of thought, of a sense of safety.

NT: I am looking at these photos of the helicopters against the sky–can you help orient me–where are you standing when these were taken?

JA: These photos are taken from two locations a few blocks apart. One is taken from my front porch and the others are while walking near Trumbull and Porter streets in Corktown.

NT: Whose helicopters are these and what are they doing?

JA: I took these pictures in the days after the November election. It seemed such a delicious irony that a crowd of angry white suburbanites fixated on a lie and steeped in conspiracy theories were being surveilled by a black helicopter, the star of conspiracy theories about the government that was all the rage in the 90s. It also demonstrated a particular type of race and class dissonance, in which the police and their tools were still viewed as aligned despite being heavily surveilled. Black helicopters are fine as long as they are regularly deployed to surveil other people and other places. DPD Chief James Craig went out of his way to praise the election protestors practicing their first amendment rights while he had spent the summer demonizing Detroit Will Breathe and the protests for Black lives.

This helicopter is a Detroit Police Helicopter. This was shortly after the November election and they were flying quite low over the neighborhood for a few days. They seemed to be part of the air surveillance teams that were monitoring white suburbanites protesting the election at the TCF Center downtown.

This helicopter and those of other security agencies have been a constant presence in the neighborhood since the murder of George Floyd and the protests for Black lives that began shortly after in Detroit.

George Floyd was murdered by the Minneapolis Police on May 25, 2020. In Detroit, calls went out for a demonstration at the end of that week. It was an incredibly diverse and large assembly. The energy in the crowd was incredible, it was radiant. There was a jubilance fueled by righteous anger and mixed with the first real taste of being in communion with so many after months of isolation.

Yet it was also a bizzarro pandemic world. Our family joined the march on Michigan Avenue as it entered Corktown. There were most of the familiar faces and groups that frequent Detroit protests and there was a large contingent of young white people in the march. At the same time, there were also more disturbing observers. Fully armed boogaloo boys decked out in Hawaiian shirts and camo with AR-15s and signs about how their “movement” stood with George Floyd. Other armed observers included out of shape militia members and bearded guys with rune tattoos recording everything on their phones. It is not unusual for a few ideologically opposed individuals to show up or happen upon a protest. It had been unusual for these groups to organize and congregate fully armed at these events. This showing by fascist, neo-nazis, right wing militias, racists, and violent extremist, accentuated the underlying menace of the risk of the virus, but also the overt emboldening of these violent extremist by the now former president, his administration, and members of his party. There is a clear line from the 2016 campaign to Charlottesville to the lockdown protests at state capitols to the nationwide presence of armed racist and fascist groups at local demonstrations over the continued killing of Black people by the police. That narrative line currently culminates storming the US Capitol in the aftermath of the 2020 election, but the invitation for these groups to emerge from the shadows in which they have long been organizing was years in the making.

I became a bit obsessed with the helicopters because during the first march in May the police were using the helicopter very aggressively by swooping low after DPD had created a loose kettle at the intersection of Michigan and Rosa Parks.

The initial DPD response to the protests in the first weeks was rather violent. They attempted to use brute force and numbers to intimidate protestors. It didn’t work much to the protestors and organizers credit as they marched for over 100 days.

The DPD helicopters were in the air for the majority of those marches.

NT: What are the other presences at the time–can you hear the sound of the rotors? What are the sounds at ground level (ie, can you hear voices, either responding to the helicopters presence or other?

JA: The rotors are loud. You can hear them coming. At this point, staying at home in the pandemic, and the frequency of these flights, I can now identify the various helicopters by the sound of their approach. The DPD uses a refurbished Kiowa helicopter that was acquired as military surplus. The Kiowa was deployed in Vietnam and used as a training helicopter in the decades after. When the military switched to a newer helicopter the remaining were sold as surplus. The US Customs and Border Patrol has the most intimidating sound. It is military grade Blackhawk helicopters and the power of the engines rumble the ground even at altitude. It shakes the house if the pass is relatively low. This helicopter was deployed more frequently after DPD Chief James Craig started appearing on Fox News and hosted then US AG Bob Barr and the justice department in the late summer or early fall.

The constant hum of helicopters at night in the summer and into the fall became a soundtrack to the pandemic.

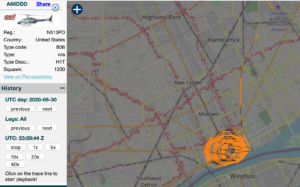

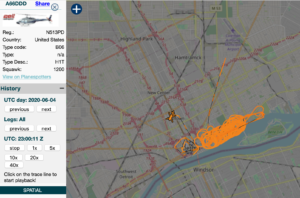

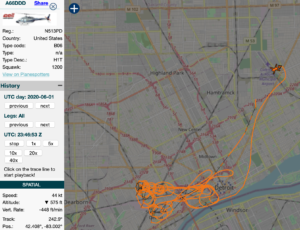

There are a few of the flightpath images that circulate across a wider map, and then there are some where the flight paths really suggest tracking back and forth across a tight geography. What are each of these cued to in terms of what is happening on the ground at that time?

The wider flight paths show more routine operations for DPD helicopters. The tighter flight paths correspond directly to the protests for Black lives. DPD would hold position over the rally and then follow the march.

Postscript:

I spent about six years as a reporter in the early 2000s. I spent nearly a year covering a beat called night cops in Albuquerque, NM. This meant I spent nights following cops around to shootings and accidents, covered events such as protests, and investigated stories around police misconduct and wasteful spending. I found the typical news style of covering cops to be pretty boring – show up to a scene, stand in the pen they had cordoned off for the press well away from the event, and then wait for the spokesperson or commanding officer to tell you what was going on. As a reporter, it was about as close as you could get to propaganda, writing a version of events based only on official statements from the police without seeing what happened or talking to those involved. If you wanted to do that job right, you spent a lot of time after the fact tracking down family members and witnesses in an attempt to understand what happened. I was still a police reporter in the run up to the second Iraq War and by that point I had mostly abandoned sitting behind police lines and relying on spokespeople. I chose to embed with demonstrators and protestors in regular anti-war protests. I was attempting to cover the activities of police as experienced by demonstrators. It fundamentally changed the way I understood police tactics and this experience continues to shape the way that I understand, engage, and experience public demonstrations and protests. The ways in which the choice to kettle opens the avenues for police to justify gas, batons, and pepper balls without violating their rules of engagement or to justify their use of force even if excessive. How the public relations tool of horse mounted police become terrifying weapons of hooves and long wooden batons wielded from on high. The ways in which a crowd fleeing police aggression provides the cover for great aggression that does not distinguish between press, protestor, medic, or legal observer. Finally, to the point of the questions here – the way in which a helicopter can be used not only to surveil but to intimidate and to emphasize who has the power of violence and that the use of that violence is an ever-present threat.

That first demonstration has this incredible energy, it also has this menacing layer of armed white supremacist on sidewalks and parking lots along the route, and then it has the police which are out in full force but obviously on their heels. The cops are rapidly blocking off streets, the mounted patrol is brought in, and the helicopters are circling at lower and lower altitudes. By the time the demonstrators reach Rosa Parks the police have begun to kettle. There is a police line on Michigan Avenue and on the southern side of Rosa Parks. There is a heavier presence on the north side of Rosa Parks with multiple police vehicles between Michigan Avenue and any possible entrance to the freeways. It seemed the police assumed the demonstrators may try and occupy the freeway and decided to slow the crowd and to try and direct it away from this action. These kinds of assumptions and this dark imagination really define much of the Detroit Police Department and City of Detroit’s approach to the protests over the next few months. There are assumptions of the worst possible motives, seemingly random shows of force, and their very own conspiracy theory that the demonstrators themselves are engaged in a conspiracy and are primarily agitators from outside the city. There is no point throughout 2020 that DPD or the City demonstrate any self-awareness or understanding of the demonstrators and their demands. They chase ghosts invoking Portland and Seattle and other right wing talking points about “urban riots” to justify their crackdowns. They spin fantasies about their record and the services they provide to residents though their own data, which is questionable. All of it raises the persistent questions about their performance, the cost to the city, and how those whose job is nominally defined and salaries justified on their alleged ability to lower crime rates remain employed for years without accomplishing those goals.

It is the initial kettle where things first breakdown and the deep antagonisms that defined the first weeks of protest crystalize. The crowd in the intersection swells as more and more people walking down Michigan Avenue reach Rosa Parks. Police grab a protestor and place him in the back of a car. Some of the crowd swarms the cruiser. The crowd overtakes the police lines and some smash windows of empty police cars parked in the middle of Michigan Avenue (what police often refer to as bait cars. Empty police vehicles unattended in the midst of protest near a site where police tactics are used to agitate the crowd). The crowd demands the arrested demonstrator be freed. The police refuse. Mounted police charge in to break up the crowd. The police helicopter swings low over the intersection drowning out the noise of the crowd as it banks tightly around it. The helicopter rises as it moves away before maneuvering over the crowd again. As the tension rose, we had been moving steadily back and once the horses arrived we walked back toward our home two blocks off Michigan Avenue (I am still quite skittish around police horses in crowds nearly 18 years after nearly being stomped and threatened with a baton while laying on the ground holding up my press badge and tending to a man hit in the head by a tear gas canister and trying to shield his five year old daughter from the horses and baton). Multiple police cruisers were now speeding down narrow neighborhood streets without sirens or lights and with little regard for residents or children playing in front yards. The helicopter continued at low altitude continually buzzing the neighborhood as it followed the demonstration deeper into Southwest Detroit and back. For those of us living in proximity to the Detroit Police headquarters on the western edge of downtown, helicopters would become the sound of the summer. DPD helicopters, a Michigan State Police helicopter, US Border Patrol Blackhawks, news helicopters, and a few that could not be identified.

The helicopters held my attention because they were a constant through the late afternoon and evening. They were there whether joining a demonstration or sitting in my backyard. Even as the protests transitioned away from daily to weekly in the late fall, the helicopters continued on a nightly basis.

-Joshua Akers

Joshua Akers is an Associate Professor of Geography and Urban + Regional Studies at U of M -Dearborn. Akers’ research and writing examines the intersection of markets and policy and their material impacts on urban neighborhoods and everyday life. He is particularly interested in the transition of property markets in the wake of the financial crisis. This work can be found in Urban Geography, IJURR, and Environment and Planning A. He works directly with organizations and activists focused on housing and tenancy issues in Detroit. He developed a web mapping tool to assist communities working to slow speculation and its effects on local neighborhoods. This work may be found at propertypraxis.org. It is part of the Urban Praxis Workshop, which he directs. He is a contributing editor for Metropolitics, a journal of public scholarship.